Climbers in western Colorado know the thrill of working their way up the tricky rock faces of desert canyons and mountain crags. But those who enjoy practicing the sport in remote areas worry they could lose safe access to some routes, if a key piece of safety equipment is banned on some public lands.

They've enlisted the help of Congress to try to head off proposals by some federal land managers that could define fixed anchors — often a bolt drilled into the rock that climbers can affix ropes to — as an “installation.” That would prohibit them in some places.

In order to preempt those rules, which are being considered by the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, among others, congressional leaders are stepping in to make it clear that the practicality of permanent climbing fixtures isn’t contradictory to the philosophy of protecting pristine wilderness.

“As a visual impact, you're talking about something the size of a golf ball, and a lot of times we'll camouflage the anchors, especially if we're in a more sensitive area,” said Randall Chapman, a climber in Western Colorado who supports the congressional effort. “And, even as a climber, I have difficulty finding those anchors sometimes and that's what I'm looking for.”

But the agencies targeted by Congress argue the bills are premature and unnecessary.

Low impact, high reward

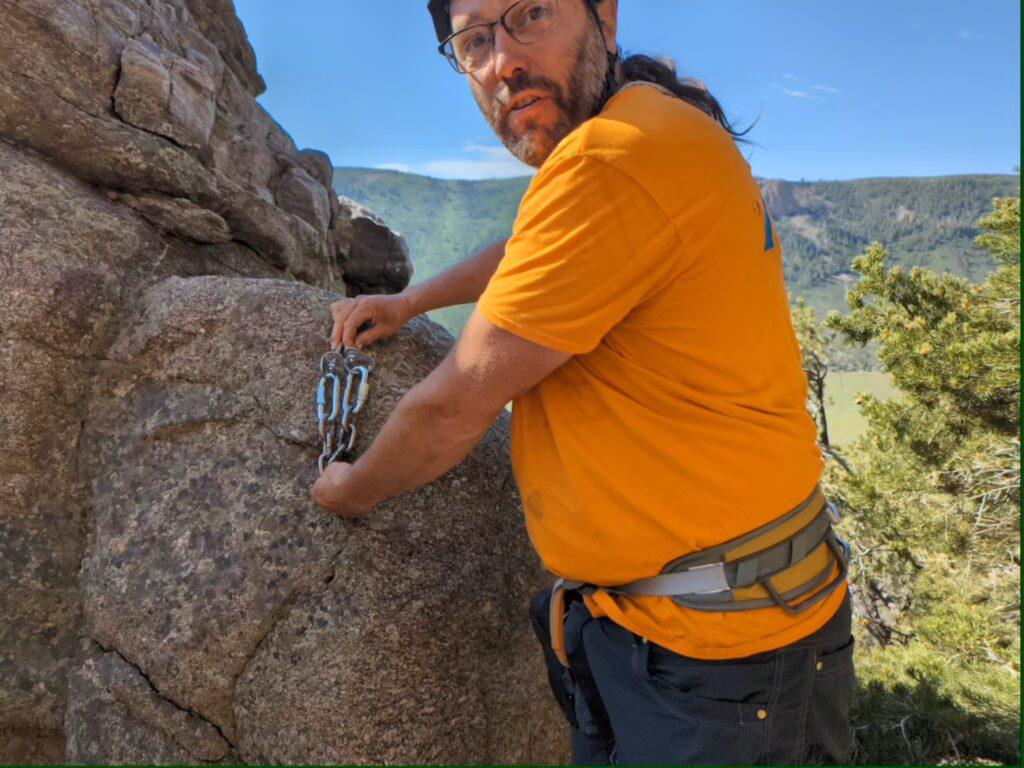

During a recent trip to Unaweep Canyon, Chapman and his friend Bob Eakle hauled heavy backpacks of gear up the steep terrain in order to install anchors for a beginner route on a formation called the Beehive. The anchors, Chapman said, make the climb safer for beginners. And in many cases, they argue, leaving something permanent in the rock beats the alternatives.

”If we have a fixed anchor there, then that means thousands of people can use that fixed anchor. Whereas if we have slings around a tree or around a horn in the rock, then maybe a couple hundred people could use it. Or, if it's not popular, the sun will rot that before anybody else gets to use it. As far as, like, environmental impact, it's a lot friendlier to just put a couple bolts in.”

He also points out that people who plan to rappel back down after climbing need to be able to bring all of their gear back with them, something the fixed anchors make possible.

Chris Righter, a member of the Western Colorado Climbers’ Coalition who has also climbed at the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, said there’s not much debate in the climbing community about fixed-anchor use.

“Probably (there are) a few people who don't like a lot of fixed anchors in the wilderness, but I'd say that's like maybe 1 percent — if that — of the climbing population,” Righter said. “And I think the general concern (of) people who didn't want the fixed anchors in the wilderness was that they were afraid that it would be kind of an eyesore or something that people would see.”

In Colorado, a proposed update to the Black Canyon of the Gunnison’s Wilderness and Backcountry Management Plan has driven much of the discussion in Colorado’s climbing community. Groups like the Access Fund, a Boulder nonprofit that supports climbing access, seized on proposals in the draft update that would affect fixed anchors.

That Aug. 2022 draft says “structures and installations diminish the undeveloped quality of wilderness, while actions that manipulate the biophysical environment detract from the untrammeled and solitude or primitive and unconfined recreation qualities of wilderness.”

The Access Fund questioned whether the Black Canyon proposal, and similar policies contemplated in other Wilderness Areas, might be "a war" on wilderness climbing.

Lawmakers bore into the matter

Colorado Sen. John Hickenlooper got a first hand taste of the issue when he went climbing with Tommy Caldwell, a legend in the climbing community, during his first year in office.

The goal of the photo opp was to highlight climate change legislation, but Hickenlooper learned a bit about the sport, too.

“He pointed out how unobtrusive anchors and bolts are. And yet to actually climb safely in a variety of locales, you need these assist areas so you don't have more terrible accidents,” he recalled.

For Hickenlooper, a longtime booster of outdoor recreation, it makes complete sense for Congress to step in and clear up any confusion or questions about whether fixed anchors can continue to be used across many types of federal land.

“We wanted to make sure there was absolute clarity that this is an essential part of wilderness areas as well as our National Parks,” Hickenlooper said.

Back in Washington D.C., Hickenlooper got language that would allow the continued use of fixed anchors for rock climbing in wilderness areas added to a bill that is now awaiting a full senate vote.

Over in the House, a bipartisan pair of Western lawmakers, GOP Rep. John Curtis of Utah and Colorado Democrat Joe Neguse, is working to pass similar legislation. During a hearing on the PARC Act, Neugse said it’s simply about ensuring a clear standard for a practice that’s been going on for years.

“There are a number of national forests that have in effect changed the rules of the game, right? They’ve begun to treat these fixed anchor devices differently than they have been treated previously,” he said.

Curtis added it’s about “creating a predictable standard for the rock climbing community, who have been using wilderness areas since their inception, and, if I might say so, are among our most predictable caretakers of these wilderness areas and who care deeply about protecting them.”

The House version of the policy is also awaiting a full vote in the chamber.

But this idea may have a hard climb ahead of it. The National Forest Service and the National Park Service have both raised concerns, saying it would, in effect, be changing the Wilderness Act by allowing permanent installations in areas that are supposed to remain as pristine as possible.

And earlier this year, Chris French, Deputy Chief of the National Forest System, said in the hearing that the policy is also unnecessary, because they’re already working on guidance around the issue.

“I believe you’ll see that almost every issue that’s been brought forward in your bill will be addressed,” he assured the House committee members.

According to a spokesperson for the Forest Service, the agency is close to publishing the long awaited draft guidance, which would then be open for 60 days of comments. But they don’t have a set timeline for how soon that will be out.

While the halls of Congress are far from the cliffs of western Colorado, climbing could still be an apt metaphor for how bills become law. Hickenlooper says lawmakers go up on a route thinking it’s straight forward, “and then they find they can't get through a certain point and they have to go climb back down and, and find a new route. That's like legislation.”

Right now, with bipartisan support in both chambers, the approach for the bills looks like it should be clear. But opposition from the agencies means there may still be some tricky bits ahead.