Imagine practicing a form of spirituality that connects you to nature and the well-being of your community. It’s not solely based on a certain set of beliefs. Instead, you see your life is intertwined with the natural world.

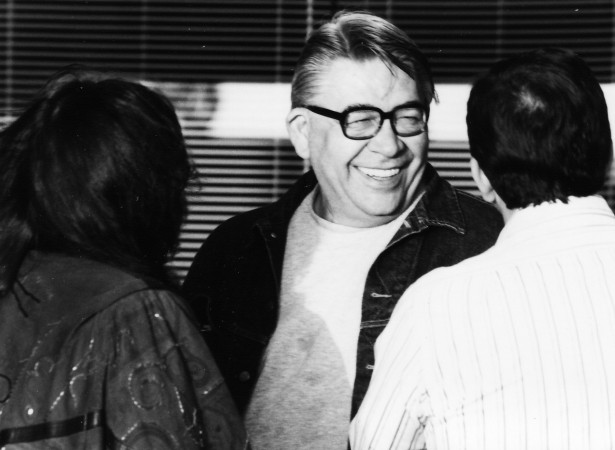

Author Vine Deloria Jr. writes about this in “God Is Red: A Native View of Religion.” The book was reissued in 2023 for its 50th anniversary. It continues to explore Indigenous and Native views of spirituality and religion. The book brings a diversity of thought to religion and sheds light on the importance of how to respect Native traditions and our environment.

Deloria was a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and went to law school at the University of Colorado Boulder, where he later taught in the 1990s. He died in 2005 at 72 years old.

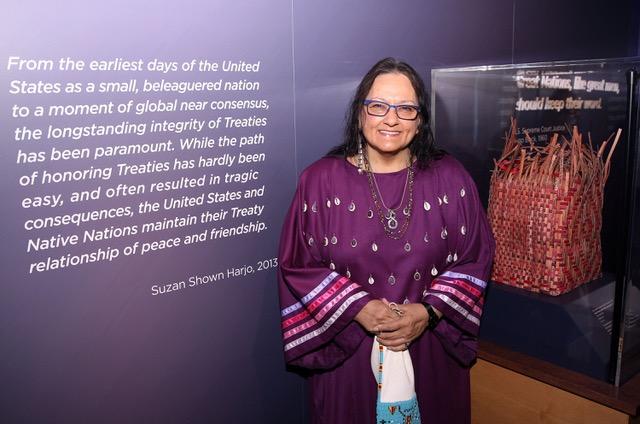

Writer, curator, and policy advocate Suzan Shown Harjo, a citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes and also Hodulgee Muscogee, wrote an essay in the latest release of Deloria’s book. As did Daniel Wildcat, Yuchi member of the Muscogee Nation of Oklahoma and professor at Haskell Indian Nations University.

The two spoke with CPR’s Hayley Sanchez about what “God is Red” means to them, their friend Deloria, and why the text is still relevant today.

Read the interview

This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Hayley Sanchez: You both worked closely with Deloria. What do you think he would say about where things stand in terms of Native spirituality today?

Daniel Wildcat: Well, I tell you what — in some places, it's the best of times. In some places, it's the worst of times. I think we do see in several nations across the United States, a real interest in returning to traditional ceremonies, honoring sacred places. That's real; That's manifesting itself in some places. At the same token, we're hardly a homogenous group of people — American Indians and Alaska Natives for American Indians. We also see a number of tribes that seem increasingly dominated by business councils that often seem to want to emulate the modern settler view of economics.

So I think it depends on the community you're looking at. And I think Vine was always very hopeful that young people would start looking back to their own religious or spiritual ceremonial traditions. I think that is happening. I see a lot of young American Indian students at Haskell Indian Nations University who are really committed and involved in that now. So I think there's reason to be cautiously optimistic. Yet we still seem to have the major forces of this economic notion of wealth, and unfortunately, even health, that I think is very real. That's always a struggle, I think, for our nations to figure out how they can really exercise their sovereignty in the world we live in today.

Tell us about what Deloria’s “non-alter-Native” worldview is and the three ways we can improve our livelihood.

Wildcat: We always talk about alternatives and things that we should look at, but I always like to point out, for us, it's not “non-alter-Native.” But [Deloria’s] views were always very much about how we can look to our own intellectual and spiritual traditions. And I think that's one of the key things that he emphasized throughout his work.

He had more than one essay where he used this idea of kinship with the plants and the animals and the living features of the world we live in today as being very important. I think you put those two things together and look to our own traditions for answers, then recognize that we'd be much better off living in a world full of relatives than one of resources.

And I think for Deloria, there was always a hope that if young Indigenous peoples would look to those traditions, the powers of the world we used to live in are still there. We've just become so insulated from those in the modern technological convenience of the world we live in, that I think he was always advocating that, look, we can do better. And maybe it's not about sustainability so much as it is about resilience.

Daniel, you write that you hope this edition of the book will find a new generation of readers who are interested in using wisdom from Einstein, where “One cannot fix problems with the same kind of thinking that created them.” What do you mean?

Wildcat: We are sort of caught between two kinds of dominant answers, particularly when we look at global climate change. One answer is we're gonna have to address this big system; It's gotta be a large institutional change. And the other is: no, we can't do that and we've got to work from the ground up. Everything's gonna have to be community-based and really highly invested in community.

Again, it's that kind of dichotomous thinking: it's gonna either be this way or that way. I think one of the things that Indigenous, intellectual traditions bring us is the notion that that binary, that dichotomous kind of thinking has no place in our traditions.

And we might see some ways of dealing with things that the dominant society seems incapable of doing. Without going into the specifics or details of our own ceremonial traditions, there is general wisdom that comes out of those things that we're not gonna talk about, we don't share, but that we could show people there's a different way of thinking about the world and the first peoples of this land might have some wisdom that would be useful if you could leave your prejudice behind.

Suzan, you're an activist. How did this book influence your activism when it first came out, and how does it influence it now? How did it spark dialogue within Indigenous circles and also among people who are not Native American or Indigenous?

Harjo: Like many of the books and articles and other writings that Vine did, I first heard them from him or heard drafts or pieces. So I have an almost kaleidoscopic memory of Vine’s books because most of them I didn't read first. I heard them in whole or in part. On telephone calls… [laughs].

And sometimes I'd say, ‘Oh, that's really terrific.’ And he'd say, ‘No, I think I can do better’ and he'd hang up. He would call back in a few hours with something indeed better. And so how did he influence me? From the moment we met at the beginning of our 40-year friendship, he influenced every part of my life.

He encouraged me and influenced me as a writer and as a radio producer. He influenced me as a person who wanted to advocate and generally make things better; and [he encouraged me] to be very specific about what I wanted, where I was going, what I needed. So next to my parents, and my brothers, and my husband, he was one of the most influential people in my life.

One of the main comparisons throughout the book is how Western religion is different from Native Spirituality. And Suzan, what are the most significant differences and similarities you see between these vastly different worldviews?

Harjo: Well, all religions have the same beliefs, have the same values: don't murder anyone, don't hurt a child, don't hurt old people, don't hurt vulnerable people, don't do anything bad to the people you live next to, and be good to your parents. And honor your people who've come before you, honor the people who are to come. All of these are held in common with practitioners of religions the world over.

The difference is in style. The difference is in collective attitude. The differences in how people behave with one another and with everything that they affect, and that affects them. So when we say we're praying for the good day for the world, we really mean that. We mean for everyone, for everything; for Mother Earth and all her children.

And like people of many religions, we are close relatives of animals and birds and plants and things that people don't even think are living, like rocks. We have great relationships with all of Mother Earth if we're fortunate to have been brought up that way, or to have come into it in the right way.

As a newcomer, they need to ask permission. They need to approach with respect, ask permission, ‘What are the protocols? What are the ways that I should behave?’ And boy, wouldn't it be a more wonderful world if people did that? Just that and didn't just disregard the answers.

Deloria advocated for federal law reform when it comes to religious freedom. In 1992, he spoke to people in Portland about how Native Americans face threats to religious freedom by not having access to sacred sites or religious sacraments.

Vine Deloria Jr.: I talked to an elder about this problem and he said, ‘Well, we gotta make it clear. We're not going out to these isolated places to pray for Cadillacs or weight loss or any of the things that the Christians are praying for.’ [Laughs] ‘We're going out there, to pray for all the mankind and the earth. And that's who we're praying for. We do not want to be wealthy. We do not want to drive BMWs.’ I said, ‘Well, I’ll try and convey that message.’

That audio is courtesy of the City Club of Portland. Suzan, you not only worked closely with Deloria, but you were friends with him too. Tell us about how he used humor in his writing and advocacy work.

Harjo: It was his mainstay before he got into anything serious; he would joke around with people. He would use humor throughout every speech he ever made. Even those that were very solemn or that were angry or highly technical. He always relied on humor and was a master at it. He was a jokester and a humorist.

Religious pluralism, it's the idea that multiple religions can coexist in society. And the founding fathers built our country on this idea. Talk about the ways where we're still really far from that being a reality.

Harjo: A few of the founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin had that idea about religious pluralism. But most of the founding fathers had an idea of manifest destiny by the one true God being Christian and Protestant. And that was the way the world was. The idealists were interested in a government that was not controlled by religion. And that was the point of it. But most of the people envisioned absolute control by the Christians. And you see that to the present time.

What are some examples of how Native or Indigenous people are restricted or forbidden from freely practicing their spirituality? Something that comes to mind is sacred lands being privately owned or government-owned and not respecting Native burial grounds.

Harjo: Anything that the white people thought was of value they coveted. They wanted it and were willing to kill Native people for it. And so we have lots of lands where we buried our ancestors and thought that that would be their final resting place. Instead, a lot of non-Native people commodified our ancestors and precious things. They were buried with their shoes, their outfits and jewelry, and anything that was personal and was given a value in money terms. And then that was applied to a lot of the lands that were stolen: the value of the things, the people, and things that were underneath it.

Indigenous people, they see the environment as sacred. All living things are connected. How can these views inform our environmental stewardship today?

Wildcat: Some of the best and brightest physical scientists today who are dealing with global climate change, I think that they are increasingly coming around to this view that says, ‘Hey, this isn't a machine that needs to get fixed — the Earth — but really it's going to need something much more comprehensive.’

Increasingly I see scientists who are more willing to consider very deep relationality between different factors that all contribute to climate change. They now realize it's gonna take not just a physical science solution, but as I've said in my writings, we need a cultural climate change. We need that Einstein quote I'm fond of. We've gotta have a new lens to look at the world. In some ways, I would advocate for the new lens to be a very old lens: it's the lens of the first peoples of this land.

What actions or policies do either of you hope are on the horizon to address these environmental concerns?

Wildcat: I am hopeful, cautiously hopeful, that there will be a majority of people who recognize not for their narrow self-interest, but in the interest of their children and grandchildren, that we've got to do something different in terms of energy consumption and where we get our energy from. I think that policy movement is still gonna be very important for us to keep that advocacy for the decarbonization of our energy future.

Harjo: It is a way of life that you have to think very far ahead and very far back. You respect and are provident about your past generations — three generations back and three generations forward, and your own time. So it's still that seventh-generation idea. And you weigh the consequences of what you're doing today against all of that. Will it honor the ancestors? Will it respect the ancestors? Will it serve us today? And are we doing something that's going to provide for our children and their children and their children and their children? Or are we doing the opposite and acting as if everything is a resource?

It always starts with attitude, then language, and then action. So if we're thinking of ourselves and our ancestors, and everything we drink and walk on, and everything we live next to as for sale, then we're all in big trouble. You have to have people who are leading with their wisdom and leading with their words, talking about the language that needs to be adopted.

So we're always talking about relations rather than resources. Thinking more collectively, and thinking more in terms of the wholeness of our lives, is the direction that I think everyone needs to go in. And the climate crisis is where we're seeing the results of people not thinking things through and not trying to decide to do good.

Describe the main message you each hope people take away from reading “God Is Red.”

Wildcat: So I am going to read a passage from the closing paragraph of the book. Vine, Suzan, and I have talked about this often — some people have a gift or are given a gift to see in the future. Vine never talked about this or anything, but his work is always so present to contemporary issues that we're dealing with now. And, I wanna end with this from the last paragraph of “God Is Red,” written 50 years ago, 'cause it rings as true today as it ever has. It says:

“The planet itself calls to the other living species for relief. Religion cannot be kept within the bounds of sermons and scriptures. It is a force in and of itself. It calls for the integration of lands and people in harmonious unity. The land's weight, for those who can discern their rhythms. The peculiar genius of each continent, each river valley and rugged mountain, the placid lake for all call for relief from the constant burden of exploitation who will find peace with the lands, the future of humankind, lies waiting for those who will come to understand their lives and take up their responsibilities to all living things. There's an opportunity.”

Increasingly, I am hopeful, particularly among our young people, that they're gonna see it's time to take up our responsibilities for all living things for the life of this mother earth.

Harjo: I think Vine should have the last word. [Laughs]

- Meet the man chosen to strengthen ties between CU Boulder and Indigenous students

- 3 decades later, Western Colorado University is trying again to return looted remains to rightful home

- Colorado schools dramatically adjusting to teach migrant students – many who’ve never been to school before

- New state historian wants to diversify understanding of Colorado’s past, present, and future