Colorado voters will not get to decide this November on a constitutional amendment to allow lawsuits over child sexual abuse that occurred in the 2000s and earlier.

An effort by Democrats in the legislature to put the measure on the ballot fell one vote short of securing the required supermajority to move forward. In a vote Wednesday, it had the support of all 23 of the state Senate’s Democrats, but the chamber’s 12 Republicans were able to block the measure.

The proposal aimed to allow “lookback” lawsuits that are currently barred in Colorado.

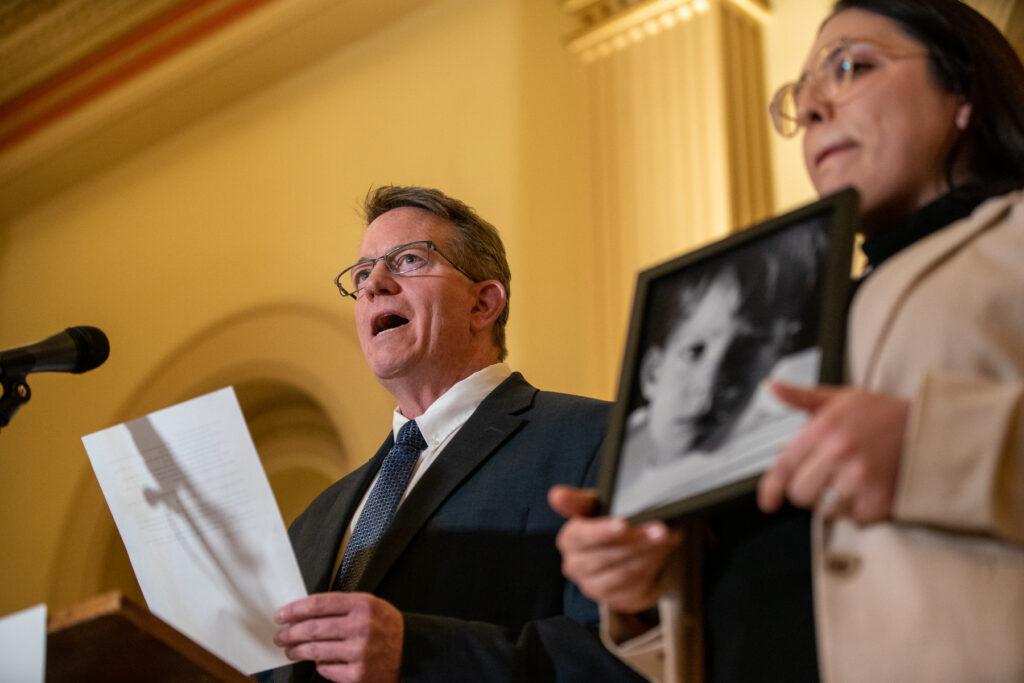

“The existing law of the state of Colorado has failed these victims. The survivors deserve the opportunity to seek justice, no matter when their abuse occurred,” said Sen. Jessie Danielson, a Democratic sponsor of the resolution.

While most legislative action only requires a majority, attempts by lawmakers to amend the Constitution have to clear a higher bar. Democratic lawmakers, advocates, and individual survivors spent months trying to win over at least one Republican senator, but all came to naught on Wednesday morning.

Senate Minority Leader Paul Lundeen, a Republican, described his “no” vote as perhaps the hardest decision in his legislative career and said that hearing stories of abuse “almost causes our hearts to burst” with empathy for the survivors. But in the end, he said, opening the door for these lawsuits would not be legally sound.

“Altering the statute of limitations after the fact could be viewed as an arbitrary change to legal rights,” he said.

Angie Witt, who described suffering 15 years of abuse in Colorado, kept tabs on the proceedings from her home in another state. “I’m watching … Tears streaming,” she wrote in a text message to CPR News. “Longing for one Republican to be brave and vote yes.”

Sen. Bob Gardner, a Republican, said he had “agonized” over the question. He would have supported allowing lawsuits against individual perpetrators, but not the organizations that were connected to them, he said.

“It is not out of some misguided desire to protect sexual predators,” he said.

Gardner continued: “We’re making a decision about whether to change our constitution to remove vested rights not only for sexual predators — which bothers me not — but also vested rights for all of the organizations for whom they were associated, worked, volunteered …. Each and every one of those organizations, and the cost is going to be large.”

The proposed constitutional amendment would not have directly allowed the lawsuits to begin. Instead, it would have set the stage for the legislature to pass a future law to allow those suits.

An amendment was a way to resurrect an earlier law

This is not the first time the legislature has weighed this issue, although with a very different outcome.

In 2021, state lawmakers passed a bill retroactively lifting the statute of limitations on civil suits of this kind. It attracted strong Republican support, although they also didn’t have the numbers to stop it. But it was struck down by the Colorado Supreme Court in 2023, which ruled the legislature didn’t have the authority to make this kind of ‘lookback’ law.

This year’s effort would have asked voters to give the legislature that power, on this specific issue. But unlike the 2021 law, it did not set specific details or requirements around what lawsuits would be allowed, instead leaving that question to a future legislature. Some Republicans said they were hesitant to open the door for future legislation without knowing the details.

Democrats rejected those concerns.

“Why should we create barriers to justice for a child that has been sexually abused?” asked Sen. Rhonda Fields, a Democratic sponsor of the measure. “Either we’re for justice or we’re not. Either we want to protect children, or we’re not.”

The measure’s chief opponents included the Colorado Catholic Conference and insurance carriers, among others. Supporters include the Colorado Coalition Against Sexual Assault, the Colorado Association of Chiefs of Police, and the tribal councils of the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute, among others.

Reformers face a longer, harder route ahead

If the measure had passed the legislature, it would have appeared on the November ballot, where it would have needed the support of 55 percent of voters to pass.

With the measure’s failure, reformers and survivors instead will have to look at other options.

They could begin the process of gathering more than 120,000 signatures statewide to put the question on the ballot directly, a process that could cost millions. And it is too late to begin such an effort for the 2024 election.

Alternatively, they can wait another year, hoping that this November’s election produces a new legislature willing to refer the question to voters.

The legislature has already eliminated the civil and criminal statute of limitations for many acts of child sexual abuse that occur today. However, those changes did not help people who suffered abuse as minors in the past, including some as recently as the 2000s.

For those older cases, the statute of limitations often expired within a matter of years. But it can take decades for survivors of abuse to come forward, especially because the devastating personal effects of abuse can take a lifetime to come to terms with.

Opponents of the change argued that it would be difficult for organizations to defend themselves against lawsuits from many years ago since evidence may have degraded and witnesses may not be available. But proponents countered that plaintiffs still would have to prove their case through a preponderance of evidence.

Twenty-seven states have taken some action to reopen the window for lawsuits over past abuse, according to ChildUSA.

In a statement, Senate Republicans reiterated their “principled condemnation” of sex predators and defended their record on the subject.

“The Colorado General Assembly has eliminated the statute of limitations on both criminal charges and civil claims arising out of the sexual abuse of a child, as well as vastly expanding mandatory reporter laws. If passed, the resolution would have upended numerous constitutional and legally settled rights we all depend on, including the principles of legal certainty and reliance, the principle of finality of litigation, and due process,” the statement read.